Egeria, also called Eteria, Ætheria or Etheria, was a Galician pilgrim, traveller and writer from the 4th century. The importance of this historical figure is enormous, since she is the first pilgrim and traveller that we know of, as well as being the first known writer from the Iberian Peninsula.

The documents that have been preserved state that she was originally from the province of Gallaecia in Roman Hispania. All historians agree on her high social rank: she was a woman belonging to the nobility of her time, possessing great wealth and a wide culture, a culture linked to deep religiousness, but, above all, to an inexhaustible curiosity and desire. Regarding her origins, some authors have indicated her possible connection with Aelia Flacila, the first wife of Theodosius the Great, while others point to the possibility that she was the sister of Gala, Prisciliano’s partner.

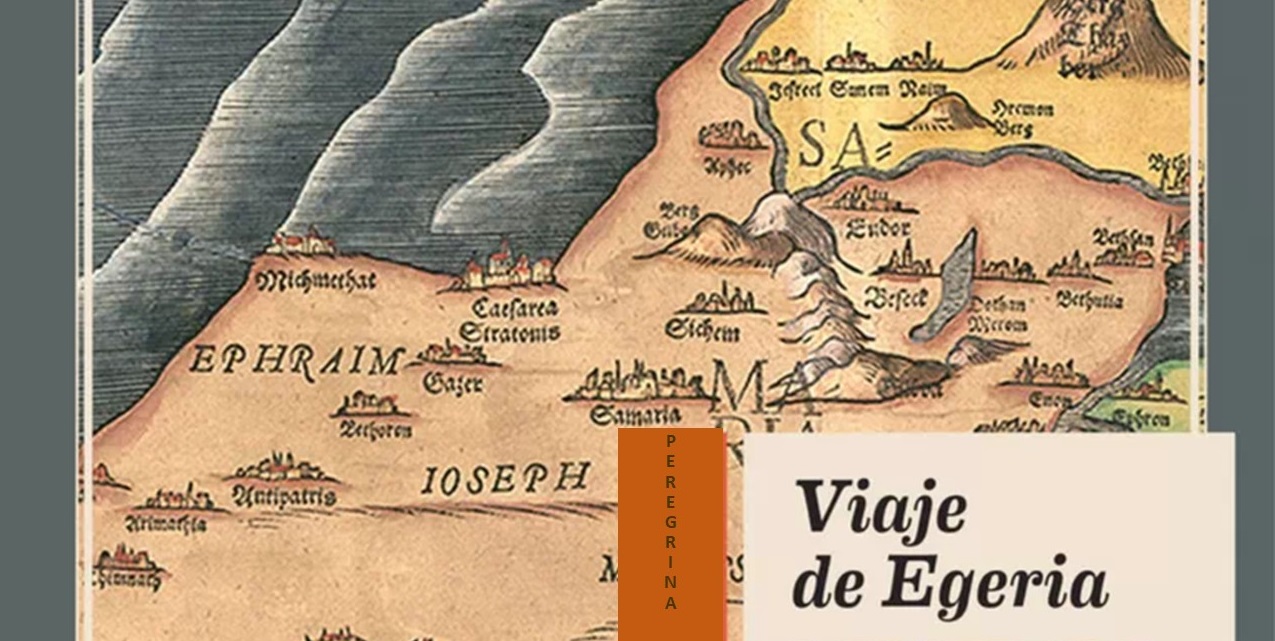

Egeria’s pilgrimage was a long adventure that took place between the years 381 and 384. Her intention was to visit the Holy Places that were known at the time or are mentioned in the Bible, which led her to cross the lands of Egypt, Palestine, Syria, Mesopotamia , Asia Minor and Constantinople.

If the journey is already extraordinary, the fact that Egeria decided to assemble her impressions in a book ‘Itinerarium ad Loca Sancta’ is even more so. It is not simply a question of a pilgrimage itinerary -the first and therefore the founder of a genre that we call ‘odeporic literature’- but of a book written in the first person, a book that already had some circulation in its time and that, far from limiting herself to mere information, she provides subjective and testimonial comments. We know this thanks to various references and, above all, to an exceptional copy: preserved in an 11th century manuscript written in the Vulgar Latin of the time, which bestows on it great philological value in studying the transition from classical to late Latin.

According to the narrative, Egeria crossed southern Gaul (France) and northern Italy, where she then crossed the Adriatic Sea, reaching the city of Constantinople (present-day Istanbul) in the year 381. From Constantinople she continued her pilgrimage to the Holy Land where she spent a long time in and around the city of Jerusalem, visiting nearby places like Bethlehem, Galilee and Hebron.

Already in the year 382, Egeria visited Egypt, where she was interested in cities such as Alexandria and Thebes, also visiting the Red Sea and Mount Sinai. She followed her itinerary through Antioch, Edessa, Mesopotamia, the Euphrates River and Syria. When three years had passed since her departure, she returned to Jerusalem from where she decided to return to Gallaecia. Of his return trip, Egeria tells us only a small part: his visit to places like Tarsus, Edessa, Syria and Mesopotamia, and the journey through Bithynia to Constantinople, the city where he concludes his diary, although stating his intention and I want to visit Ephesus.

The manuscript consists of a second part that focuses not only on the itinerary, but also on the description of the liturgy and rituals witnessed throughout the trip: mainly in the Holy Land, in the daily services, on Sundays and at Easter and during the Easter holidays.

Through this narrative we learn in detail how people travelled through the Roman cursus publicus – the 80,000 kilometre network of roads used by the Roman legions on their movements – but she also describes the difficulties that had to be overcome to travel through often inhospitable natural environments. In various lands, Egeria stayed in the so-called ‘mansio’, post houses, or in the numerous monasteries that had already been founded years before in the East, when they were barely known in the West.

However, given the difficulties that pilgrims had to overcome during the Middle and Modern Ages to cross different territories, the extension and enormous diversity of the places visited does not seem to have been a problem for Egeria, probably because thanks to the pax romana (29 BC – AD 180) a citizen of the Empire could travel from Gallaecia to Mesopotamia with almost no hindrance. However, in the text there are several clues that would suggest the possibility that she had some kind of official safe-conduct, something that allowed her, for example, to resort to military protection in especially dangerous territories.

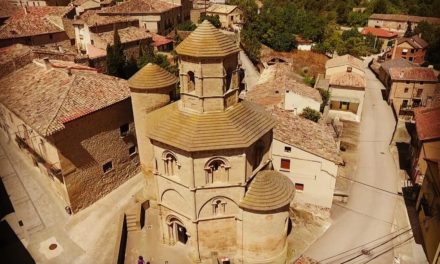

The figure of Egeria has been recovered very recently, since its itinerary remained forgotten for centuries, her identity being known only through a letter written to the monks of El Bierzo by San Valerio. Finally, in 1884, the Italian Gian Francesco Gamurrini found the manuscript in the Library of the Confraternity of Santa Maria dei Laicos (Biblioteca Della Confraternità dei Laici) in Arezzo: a 37-page parchment codex that includes other texts, such as the treatise on Saint Hilary of Poitiers on the Mysteries and the Hymns, its second part being the narration of the pilgrimage of Egeria.

The history of the Arezzo manuscript is also an adventure: we know that it was written in the monastery of Montecassino in the 11th century, from where Ambrosio Restellini, abbot of Montecassino from 1599 to 1602, later took it to Arezzo, first depositing it in the Monastery of Santa Maria de Arezzo, which in 1801 would have been closed by Napoleon, then passing to the aforementioned Brotherhood of the Laity. Currently the manuscript is kept in the museum of the city of Arezzo.

In recent years, various studies and publications have made it possible to establish the attribution of the manuscript and, today, no one doubts Egeria’s authorship. In addition, there are other references that make it possible to fill in some of the gaps in the first missing pages of the manuscript, such as the Liber de locis sanctis of Pedro the Deacon, who mentions the Galician pilgrim in his work.

Regarding Egeria, we know nothing of her life beyond what the manuscript narrates, we can only hope that she fulfilled her dreams of visiting Ephesus and finally returned to her home.